February 6, 2024

Flathub: Pros and Cons of Direct Uploads

I attended FOSDEM last weekend and had the pleasure to participate in the Flathub / Flatpak BOF on Saturday. A lot of the session was used up by an extensive discussion about the merits (or not) of allowing direct uploads versus building everything centrally on Flathub’s infrastructure, and related concerns such as automated security/dependency scanning.

My original motivation behind the idea was essentially two things. The first was to offer a simpler way forward for applications that use language-specific build tools that resolve and retrieve their own dependencies from the internet. Flathub doesn’t allow network access during builds, and so a lot of manual work and additional tooling is currently needed (see Python and Electron Flatpak guides). And the second was to offer a maybe more familiar flow to developers from other platforms who would just build something and then run another command to upload it to the store, without having to learn the syntax of a new build tool. There were many valid concerns raised in the room, and I think on reflection that this is still worth doing, but might not be as valuable a way forward for Flathub as I had initially hoped.

Of course, for a proprietary application where Flathub never sees the source or where it’s built, whether that binary is uploaded to us or downloaded by us doesn’t change much. But for an FLOSS application, a direct upload driven by the developer causes a regression on a number of fronts. We’re not getting too hung up on the “malicious developer inserts evil code in the binary” case because Flathub already works on the model of verifying the developer and the user makes a decision to trust that app – we don’t review the source after all. But we do lose other things such as our infrastructure building on multiple architectures, and visibility on whether the build environment or upload credentials have been compromised unbeknownst to the developer.

There is now a manual review process for when apps change their metadata such as name, icon, license and permissions – which would apply to any direct uploads as well. It was suggested that if only heavily sandboxed apps (eg no direct filesystem access without proper use of portals) were permitted to make direct uploads, the impact of such concerns might be somewhat mitigated by the sandboxing.

However, it was also pointed out that my go-to example of “Electron app developers can upload to Flathub with one command” was also a bit of a fiction. At present, none of them would pass that stricter sandboxing requirement. Almost all Electron apps run old versions of Chromium with less complete portal support, needing sandbox escapes to function correctly, and Electron (and Chromium’s) sandboxing still needs additional tooling/downstream patching to run inside a Flatpak. Buh-boh.

I think for established projects who already ship their own binaries from their own centralised/trusted infrastructure, and for developers who have understandable sensitivities about binary integrity such such as encryption, password or financial tools, it’s a definite improvement that we’re able to set up direct uploads with such projects with less manual work. There are already quite a few applications – including verified ones – where the build recipe simply fetches a binary built elsewhere and unpacks it, and if this already done centrally by the developer, repeating the exercise on Flathub’s server adds little value.

However for the individual developer experience, I think we need to zoom out a bit and think about how to improve this from a tools and infrastructure perspective as we grow Flathub, and as we seek to raise funds for different sources for these improvements. I took notes for everything that was mentioned as a tooling limitation during the BOF, along with a few ideas about how we could improve things, and hope to share these soon as part of an RFP/RFI (Request For Proposals/Request for Information) process. We don’t have funding yet but if we have some prospective collaborators to help refine the scope and estimate the cost/effort, we can use this to go and pursue funding opportunities.

March 7, 2023

Flathub in 2023

It’s been quite a few months since the most recent updates about Flathub last year. We’ve been busy behind the scenes, so I’d like to share what we’ve been up to at Flathub and why—and what’s coming up from us this year. I want to focus on:

- Where Flathub is today as a strong ecosystem with 2,000 apps

- Our progress on evolving Flathub from a build service to an app store

- The economic barrier to growing the ecosystem, and its consequences

- What’s next to overcome our challenges with focused initiatives

Today

Flathub is going strong: we offer 2,000 apps from over 1,500 collaborators on GitHub. We’re averaging 700,000 app downloads a day, with 898 million HTTP requests totalling 88.3 TB served by our CDN each day (thank you Fastly!). Flatpak has, in my opinion, solved the largest technical issue which has held back the mainstream growth and acceptance of Linux on the desktop (or other personal computing devices) for the past 25 years: namely, the difficulty for app developers to publish their work in a way that makes it easy for people to discover, download (or sideload, for people in challenging connectivity environments), install and use. Flathub builds on that to help users discover the work of app developers and helps that work reach users in a timely manner.

Initial results of this disintermediation are promising: even with its modest size so far, Flathub has hundreds of apps that I have never, ever heard of before—and that’s even considering I’ve been working in the Linux desktop space for nearly 20 years and spent many of those staring at the contents of dselect (showing my age a little) or GNOME Software, attending conferences, and reading blog posts, news articles, and forums. I am also heartened to see that many of our OS distributor partners have recognised that this model is hugely complementary and additive to the indispensable work they are doing to bring the Linux desktop to end users, and that “having more apps available to your users” is a value-add allowing you to focus on your core offering and not a zero-sum game that should motivate infighting.

Ongoing Progress

Getting Flathub into its current state has been a long ongoing process. Here’s what we’ve been up to behind the scenes:

Development

Last year, we concluded our first engagement with Codethink to build features into the Flathub web app to move from a build service to an app store. That includes accounts for users and developers, payment processing via Stripe, and the ability for developers to manage upload tokens for the apps they control. In parallel, James Westman has been working on app verification and the corresponding features in flat-manager to ensure app metadata accurately reflects verification and pricing, and to provide authentication for paying users for app downloads when the developer enables it. Only verified developers will be able to make direct uploads or access payment settings for their apps.

Legal

So far, the GNOME Foundation has acted as an incubator and legal host for Flathub even though it’s not purely a GNOME product or initiative. Distributing software to end users along with processing and forwarding payments and donations also has a different legal profile in terms of risk exposure and nonprofit compliance than the current activities of the GNOME Foundation. Consequently, we plan to establish an independent legal entity to own and operate Flathub which reduces risk for the GNOME Foundation, better reflects the independent and cross-desktop interests of Flathub, and provides flexibility in the future should we need to change the structure.

We’re currently in the process of reviewing legal advice to ensure we have the right structure in place before moving forward.

Governance

As Flathub is something we want to set outside of the existing Linux desktop and distribution space—and ensure we represent and serve the widest community of Linux users and developers—we’ve been working on a governance model that ensures that there is transparency and trust in who is making decisions, and why. We have set up a working group with myself and Martín Abente Lahaye from GNOME, Aleix Pol Gonzalez, Neofytos Kolokotronis, and Timothée Ravier from KDE, and Jorge Castro flying the flag for the Flathub community. Thanks also to Neil McGovern and Nick Richards who were also more involved in the process earlier on.

We don’t want to get held up here creating something complex with memberships and elections, so at first we’re going to come up with a simple/balanced way to appoint people into a board that makes key decisions about Flathub and iterate from there.

Funding

We have received one grant for 2023 of $100K from Endless Network which will go towards the infrastructure, legal, and operations costs of running Flathub and setting up the structure described above. (Full disclosure: Endless Network is the umbrella organisation which also funds my employer, Endless OS Foundation.) I am hoping to grow the available funding to $250K for this year in order to cover the next round of development on the software, prepare for higher operations costs (e.g., accounting gets more complex), and bring in a second full-time staff member in addition to Bartłomiej Piotrowski to handle enquiries, reviews, documentation, and partner outreach.

We’re currently in discussions with NLnet about funding further software development, but have been unfortunately turned down for a grant from the Plaintext Group for this year; this Schmidt Futures project around OSS sustainability is not currently issuing grants in 2023. However, we continue to work on other funding opportunities.

Remaining Barriers

My personal hypothesis is that our largest remaining barrier to Linux desktop scale and impact is economic. On competing platforms—mobile or desktop—a developer can offer their work for sale via an app store or direct download with payment or subscription within hours of making a release. While we have taken the “time to first download” time down from months to days with Flathub, as a community we continue to have a challenging relationship with money. Some creators are lucky enough to have a full-time job within the FLOSS space, while a few “superstar” developers are able to nurture some level of financial support by investing time in building a following through streaming, Patreon, Kickstarter, or similar. However, a large proportion of us have to make do with the main payback from our labours being a stream of bug reports on GitHub interspersed with occasional conciliatory beers at FOSDEM (other beverages and events are available).

The first and most obvious consequence is that if there is no financial payback for participating in developing apps for the free and open source desktop, we will lose many people in the process—despite the amazing achievements of those who have brought us to where we are today. As a result, we’ll have far fewer developers and apps. If we can’t offer access to a growing base of users or the opportunity to offer something of monetary value to them, the reward in terms of adoption and possible payment will be very small. Developers would be forgiven for taking their time and attention elsewhere. With fewer apps, our platform has less to entice and retain prospective users.

The second consequence is that this also represents a significant hurdle for diverse and inclusive participation. We essentially require that somebody is in a position of privilege and comfort that they have internet, power, time, and income—not to mention childcare, etc.—to spare so that they can take part. If that’s not the case for somebody, we are leaving them shut out from our community before they even have a chance to start. My belief is that free and open source software represents a better way for people to access computing, and there are billions of people in the world we should hope to reach with our work. But if the mechanism for participation ensures their voices and needs are never represented in our community of creators, we are significantly less likely to understand and meet those needs.

While these are my thoughts, you’ll notice a strong theme to this year will be leading a consultation process to ensure that we are including, understanding and reflecting the needs of our different communities—app creators, OS distributors and Linux users—as I don’t believe that our initiative will be successful without ensuring mutual benefit and shared success. Ultimately, no matter how beautiful, performant, or featureful the latest versions of the Plasma or GNOME desktops are, or how slick the newly rewritten installer is from your favourite distribution, all of the projects making up the Linux desktop ecosystem are subdividing between ourselves an absolutely tiny market share of the global market of personal computers. To make a bigger mark on the world, as a community, we need to get out more.

What’s Next?

After identifying our major barriers to overcome, we’ve planned a number of focused initiatives and restructuring this year:

Phased Deployment

We’re working on deploying the work we have been doing over the past year, starting first with launching the new Flathub web experience as well as the rebrand that Jakub has been talking about on his blog. This also will finally launch the verification features so we can distinguish those apps which are uploaded by their developers.

In parallel, we’ll also be able to turn on the Flatpak repo subsets that enable users to select only verified and/or FLOSS apps in the Flatpak CLI or their desktop’s app center UI.

Consultation

We would like to make sure that the voices of app creators, OS distributors, and Linux users are reflected in our plans for 2023 and beyond. We will be launching this in the form of Flathub Focus Groups at the Linux App Summit in Brno in May 2023, followed up with surveys and other opportunities for online participation. We see our role as interconnecting communities and want to be sure that we remain transparent and accountable to those we are seeking to empower with our work.

Whilst we are being bold and ambitious with what we are trying to create for the Linux desktop community, we also want to make sure we provide the right forums to listen to the FLOSS community and prioritise our work accordingly.

Advisory Board

As we build the Flathub organisation up in 2023, we’re also planning to expand its governance by creating an Advisory Board. We will establish an ongoing forum with different stakeholders around Flathub: OS vendors, hardware integrators, app developers and user representatives to help us create the Flathub that supports and promotes our mutually shared interests in a strong and healthy Linux desktop community.

Direct Uploads

Direct app uploads are close to ready, and they enable exciting stuff like allowing Electron apps to be built outside of flatpak-builder, or driving automatic Flathub uploads from GitHub actions or GitLab CI flows; however, we need to think a little about how we encourage these to be used. Even with its frustrations, our current Buildbot ensures that the build logs and source versions of each app on Flathub are captured, and that the apps are built on all supported architectures. (Is 2023 when we add RISC-V? Reach out if you’d like to help!). If we hand upload tokens out to any developer, even if the majority of apps are open source, we will go from this relatively structured situation to something a lot more unstructured—and we fear many apps will be available on only 64-bit Intel/AMD machines.

My sketch here is that we need to establish some best practices around how to integrate Flathub uploads into popular CI systems, encouraging best practices so that we promote the properties of transparency and reproducibility that we don’t want to lose. If anyone is a CI wizard and would like to work with us as a thought partner about how we can achieve this—make it more flexible where and how build tasks can be hosted, but not lose these cross-platform and inspectability properties—we’d love to hear from you.

Donations and Payments

Once the work around legal and governance reaches a decent point, we will be in the position to move ahead with our Stripe setup and switch on the third big new feature in the Flathub web app. At present, we have already implemented support for one-off payments either as donations or a required purchase. We would like to go further than that, in line with what we were describing earlier about helping developers sustainably work on apps for our ecosystem: we would also like to enable developers to offer subscriptions. This will allow us to create a relationship between users and creators that funds ongoing work rather than what we already have.

Security

For Flathub to succeed, we need to make sure that as we grow, we continue to be a platform that can give users confidence in the quality and security of the apps we offer. To that end, we are planning to set up infrastructure to help ensure developers are shipping the best products they possibly can to users. For example, we’d like to set up automated linting and security scanning on the Flathub back-end to help developers avoid bad practices, unnecessary sandbox permissions, outdated dependencies, etc. and to keep users informed and as secure as possible.

Sponsorship

Fundraising is a forever task—as is running such a big and growing service. We hope that one day, we can cover our costs through some modest fees built into our payments—but until we reach that point, we’re going to be seeking a combination of grant funding and sponsorship to keep our roadmap moving. Our hope is very much that we can encourage different organisations that buy into our vision and will benefit from Flathub to help us support it and ensure we can deliver on our goals. If you have any suggestions of who might like to support Flathub, we would be very appreciative if you could reach out and get us in touch.

Finally, Thank You!

Thanks to you all for reading this far and supporting the work of Flathub, and also to our major sponsors and donors without whom Flathub could not exist: GNOME Foundation, KDE e.V., Mythic Beasts, Endless Network, Fastly, and Equinix Metal via the CNCF Community Cluster. Thanks also to the tireless work of the Freedesktop SDK community to give us the runtime platform most Flatpaks depend on, particularly Seppo Yli-Olli, Codethink and others.

I wanted to also give my personal thanks to a handful of dedicated people who keep Flathub working as a service and as a community: Bartłomiej Piotrowski is keeping the infrastructure working essentially single-handedly (in his spare time from keeping everything running at GNOME); Kolja Lampe and Bart built the new web app and backend API for Flathub which all of the new functionality has been built on, and Filippe LeMarchand maintains the checker bot which helps keeps all of the Flatpaks up to date.

And finally, all of the submissions to Flathub are reviewed to ensure quality, consistency and security by a small dedicated team of reviewers, with a huge amount of work from Hubert Figuière and Bart to keep the submissions flowing. Thanks to everyone—named or unnamed—for building this vision of the future of the Linux desktop together with us.

(originally posted to Flathub Discourse, head there if you have any questions or comments)

August 12, 2019

Flathub, brought to you by…

Over the past 2 years Flathub has evolved from a wild idea at a hackfest to a community of app developers and publishers making over 600 apps available to end-users on dozens of Linux-based OSes. We couldn’t have gotten anything off the ground without the support of the 20 or so generous souls who backed our initial fundraising, and to make the service a reality since then we’ve relied on on the contributions of dozens of individuals and organisations such as Codethink, Endless, GNOME, KDE and Red Hat. But for our day to day operations, we depend on the continuous support and generosity of a few companies who provide the services and resources that Flathub uses 24/7 to build and deliver all of these apps. This post is about saying thank you to those companies!

Running the infrastructure

Mythic Beasts is a UK-based “no-nonsense” hosting provider who provide managed and un-managed co-location, dedicated servers, VPS and shared hosting. They are also conveniently based in Cambridge where I live, and very nice people to have a coffee or beer with, particularly if you enjoy talking about IPv6 and how many web services you can run on a rack full of Raspberry Pis. The “heart” of Flathub is a physical machine donated by them which originally ran everything in separate VMs – buildbot, frontend, repo master – and they have subsequently increased their donation with several VMs hosted elsewhere within their network. We also benefit from huge amounts of free bandwidth, backup/storage, monitoring, management and their expertise and advice at scaling up the service.

Starting with everything running on one box in 2017 we quickly ran into scaling bottlenecks as traffic started to pick up. With Mythic’s advice and a healthy donation of 100s of GB / month more of bandwidth, we set up two caching frontend servers running in virtual machines in two different London data centres to cache the commonly-accessed objects, shift the load away from the master server, and take advantage of the physical redundancy offered by the Mythic network.

As load increased and we brought a CDN online to bring the content closer to the user, we also moved the Buildbot (and it’s associated Postgres database) to a VM hosted at Mythic in order to offload as much IO bandwidth from the repo server, to keep up sustained HTTP throughput during update operations. This helped significantly but we are in discussions with them about a yet larger box with a mixture of disks and SSDs to handle the concurrent read and write load that we need.

Even after all of these changes, we keep the repo master on one, big, physical machine with directly attached storage because repo update and delta computations are hugely IO intensive operations, and our OSTree repos contain over 9 million inodes which get accessed randomly during this process. We also have a physical HSM (a YubiKey) which stores the GPG repo signing key for Flathub, and it’s really hard to plug a USB key into a cloud instance, and know where it is and that it’s physically secure.

Building the apps

Our first build workers were under Alex’s desk, in Christian’s garage, and a VM donated by Scaleway for our first year. We still have several ARM workers donated by Codethink, but at the start of 2018 it became pretty clear within a few months that we were not going to keep up with the growing pace of builds without some more serious iron behind the Buildbot. We also wanted to be able to offer PR and test builds, beta builds, etc — all of which multiplies the workload significantly.

Thanks to an introduction by the most excellent Jorge Castro and the approval and support of the Linux Foundation’s CNCF Infrastructure Lab, we were able to get access to an “all expenses paid” account at Packet. Packet is a “bare metal” cloud provider — like AWS except you get entire boxes and dedicated switch ports etc to yourself – at a handful of main datacenters around the world with a full range of server, storage and networking equipment, and a larger number of edge facilities for distribution/processing closer to the users. They have an API and a magical provisioning system which means that at the click of a button or one method call you can bring up all manner of machines, configure networking and storage, etc. Packet is clearly a service built by engineers for engineers – they are smart, easy to get hold of on e-mail and chat, share their roadmap publicly and set priorities based on user feedback.

We currently have 4 Huge Boxes (2 Intel, 2 ARM) from Packet which do the majority of the heavy lifting when it comes to building everything that is uploaded, and also use a few other machines there for auxiliary tasks such as caching source downloads and receiving our streamed logs from the CDN. We also used their flexibility to temporarily set up a whole separate test infrastructure (a repo, buildbot, worker and frontend on one box) while we were prototyping recent changes to the Buildbot.

A special thanks to Ed Vielmetti at Packet who has patiently supported our requests for lots of 32-bit compatible ARM machines, and for his support of other Linux desktop projects such as GNOME and the Freedesktop SDK who also benefit hugely from Packet’s resources for build and CI.

Delivering the data

Even with two redundant / load-balancing front end servers and huge amounts of bandwidth, OSTree repos have so many files that if those servers are too far away from the end users, the latency and round trips cause a serious problem with throughput. In the end you can’t distribute something like Flathub from a single physical location – you need to get closer to the users. Fortunately the OSTree repo format is very efficient to distribute via a CDN, as almost all files in the repository are immutable.

After a very speedy response to a plea for help on Twitter, Fastly – one of the world’s leading CDNs – generously agreed to donate free use of their CDN service to support Flathub. All traffic to the dl.flathub.org domain is served through the CDN, and automatically gets cached at dozens of points of presence around the world. Their service is frankly really really cool – the configuration and stats are reallly powerful, unlike any other CDN service I’ve used. Our configuration allows us to collect custom logs which we use to generate our Flathub stats, and to define edge logic in Varnish’s VCL which we use to allow larger files to stream to the end user while they are still being downloaded by the edge node, improving throughput. We also use their API to purge the summary file from their caches worldwide each time the repository updates, so that it can stay cached for longer between updates.

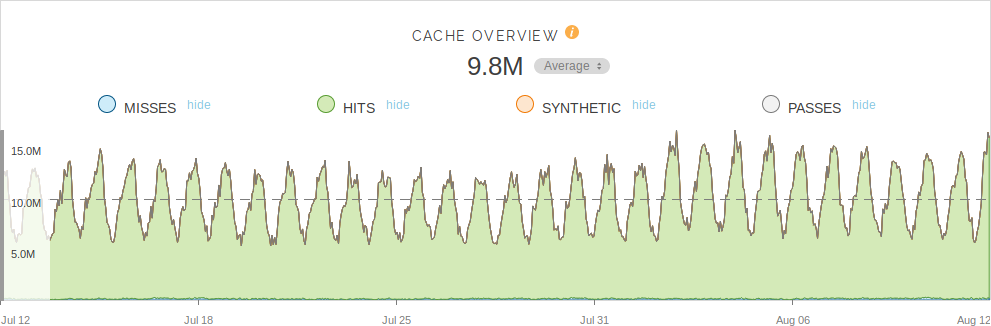

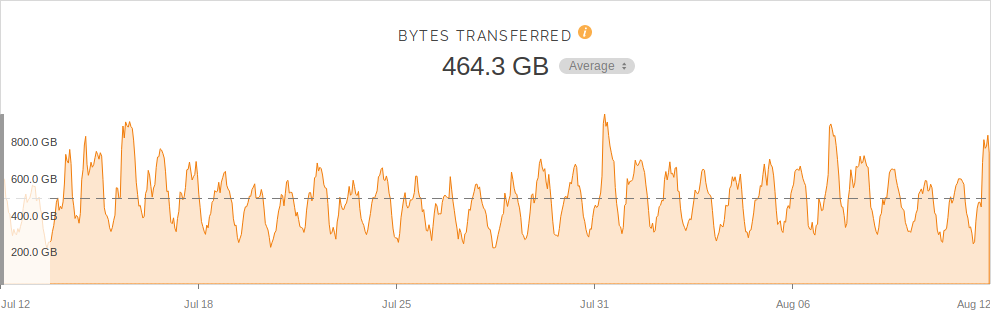

To get some feelings for how well this works, here are some statistics: The Flathub main repo is 929 GB, of which 73 GB are static deltas and 1.9 GB of screenshots. It contains 7280 refs for 640 apps (plus runtimes and extensions) over 4 architectures. Fastly is serving the dl.flathub.org domain fully cached, with a cache hit rate of ~98.7%. Averaging 9.8 million hits and 464 Gb downloaded per hour, Flathub uses between 1-2 Gbps sustained bandwidth depending on the time of day. Here are some nice graphs produced by the Fastly management UI (the numbers are per-hour over the last month):

To buy the scale of services and support that Flathub receives from our commercial sponsors would cost tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars a month. Flathub could not exist without Mythic Beasts, Packet and Fastly‘s support of the free and open source Linux desktop. Thank you!

October 15, 2018

Flatpaks, sandboxes and security

Last week the Flatpak community woke to the “news” that we are making the world a less secure place and we need to rethink what we’re doing. Personally, I’m not sure this is a fair assessment of the situation. The “tl;dr” summary is: Flatpak confers many benefits besides the sandboxing, and even looking just at the sandboxing, improving app security is a huge problem space and so is a work in progress across multiple upstream projects. Much of what has been achieved so far already delivers incremental improvements in security, and we’re making solid progress on the wider app distribution and portability problem space.

Sandboxing, like security in general, isn’t a binary thing – you can’t just say because you have a sandbox, you have 100% security. Like having two locks on your front door, two front doors, or locks on your windows too, sensible security is about defense in depth. Each barrier that you implement precludes some invalid or possibly malicious behaviour. You hope that in total, all of these barriers would prevent anything bad, but you can never really guarantee this – it’s about multiplying together probabilities to get a smaller number. A computer which is switched off, in a locked faraday cage, with no connectivity, is perfectly secure – but it’s also perfectly useless because you cannot actually use it. Sandboxing is very much the same – whilst you could easily take systemd-nspawn, Docker or any other container technology of choice and 100% lock down a desktop app, you wouldn’t be able to interact with it at all.

Network services have incubated and driven most of the container usage on Linux up until now but they are fundamentally different to desktop applications. For services you can write a simple list of permissions like, “listen on this network port” and “save files over here” whereas desktop applications have a much larger number of touchpoints to the outside world which the user expects and requires for normal functionality. Just thinking off the top of my head you need to consider access to the filesystem, display server, input devices, notifications, IPC, accessibility, fonts, themes, configuration, audio playback and capture, video playback, screen sharing, GPU hardware, printing, app launching, removable media, and joysticks. Without making holes in the sandbox to allow access to these in to your app, it either wouldn’t work at all, or it wouldn’t work in the way that people have come to expect.

What Flatpak brings to this is understanding of the specific desktop app problem space – most of what I listed above is to a greater or lesser extent understood by Flatpak, or support is planned. The Flatpak sandbox is very configurable, allowing the application author to specify which of these resources they need access to. The Flatpak CLI asks the user about these during installation, and we provide the flatpak override command to allow the user to add or remove these sandbox escapes. Flatpak has introduced portals into the Linux desktop ecosystem, which we’re really pleased to be sharing with snap since earlier this year, to provide runtime access to resources outside the sandbox based on policy and user consent. For instance, document access, app launching, input methods and recursive sandboxing (“sandbox me harder”) have portals.

The starting security position on the desktop was quite terrible – anything in your session had basically complete access to everything belonging to your user, and many places to hide.

- Access to the X socket allows arbitrary input and output to any other app on your desktop, but without it, no app on an X desktop would work. Wayland fixes this, so Flatpak has a fallback setting to allow Wayland to be used if present, and the X socket to be shared if not.

- Unrestricted access to the PulseAudio socket allows you to reconfigure audio routing, capture microphone input, etc. To ensure user consent we need a portal to control this, where by default you can play audio back but device access needs consent and work is under way to create this portal.

- Access to the webcam device node means an app can capture video whenever it wants – solving this required a whole new project.

- Sandboxing access to configuration in dconf is a priority for the project right now, after the 1.0 release.

Even with these caveats, Flatpak brings a bunch of default sandboxing – IPC filtering, a new filesystem, process and UID namespace, seccomp filtering, an immutable /usr and /app – and each of these is already a barrier to certain attacks.

Looking at the specific concerns raised:

- Hopefully from the above it’s clear that sandboxing desktop apps isn’t just a switch we can flick overnight, but what we already have is far better than having nothing at all. It’s not the intention of Flatpak to somehow mislead people that sandboxed means somehow impervious to all known security issues and can access nothing whatsoever, but we do want to encourage the use of the new technology so that we can work together on driving adoption and making improvements together. The idea is that over time, as the portals are filled out to cover the majority of the interfaces described, and supported in the major widget sets / frameworks, the criteria for earning a nice “sandboxed” badge or submitting your app to Flathub will become stricter. Many of the apps that access --filesystem=home are because they use old widget sets like Gtk2+ and frameworks like Electron that don’t support portals (yet!). Contributions to improve portal integration into other frameworks and desktops are very welcome and as mentioned above will also improve integration and security in other systems that use portals, such as snap.

- As Alex has already blogged, the freedesktop.org 1.6 runtime was something we threw together because we needed something distro agnostic to actually be able to bootstrap the entire concept of Flatpak and runtimes. A confusing mishmash of Yocto with flatpak-builder, it’s thankfully nearing some form of retirement after a recent round of security fixes. The replacement freedesktop-sdk project has just released its first stable 18.08 release, and rather than “one or two people in their spare time because something like this needs to exist”, is backed by a team from Codethink and with support from the Flatpak, GNOME and KDE communities.

- I’m not sure how fixing and disclosing a security problem in a relatively immature pre-1.0 program (in June 2017, Flathub had less than 50 apps) is considered an ongoing problem from a security perspective. The wording in the release notes?

Zooming out a little bit, I think it’s worth also highlighting some of the other reasons why Flatpak exists at all – these are far bigger problems with the Linux desktop ecosystem than app security alone, and Flatpak brings a huge array of benefits to the table:

- Allowing apps to become agnostic of their underlying distribution. The reason that runtimes exist at all is so that apps can specify the ABI and dependencies that they need, and you can run it on whatever distro you want. Flatpak has had this from day one, and it’s been hugely reliable because the sandboxed /usr means the app can rely on getting whatever they need. This is the foundation on which everything else is built.

- Separating the release/update cadence of distributions from the apps. The flip side of this, which I think is huge for more conservative platforms like Debian or enterprise distributions which don’t want to break their ABIs, hardware support or other guarantees, is that you can still get new apps into users hands. Wider than this, I think it allows us huge new freedoms to move in a direction of reinventing the distro – once you start to pull the gnarly complexity of apps and their dependencies into sandboxes, your constraints are hugely reduced and you can slim down or radically rethink the host system underneath. At Endless OS, Flatpak literally changed the structure of our engineering team, and for the first time allowed us to develop and deliver our OS, SDK and apps in independent teams each with their own cadence.

- Disintermediating app developers from their users. Flathub now offers over 400 apps, and (at a rough count by Nick Richards over the summer) over half of them are directly maintained by or maintained in conjunction with the upstream developers. This is fantastic – we get the releases when they come out, the developers can choose the dependencies and configuration they need – and they get to deliver this same experience to everyone.

- Decentralised. Anyone can set up a Flatpak repo! We started our own at Flathub because there needs to be a center of gravity and a complete story to build out a user and developer base, but the idea is that anyone can use the same tools that we do, and publish whatever/wherever they want. GNOME uses GitLab CI to publish nightly Flatpak builds, KDE is setting up the same in their infrastructure, and Fedora is working on completely different infrastructure to build and deliver their packaged applications as Flatpaks.

- Easy to build. I’ve worked on Debian packages, RPMs, Yocto, etc and I can honestly say that flatpak-builder has done a very good job of making it really easy to put your app manifest together. Because the builds are sandboxed and each runtimes brings with it a consistent SDK environment, they are very reliably reproducible. It’s worth just calling this out because when you’re trying to attract developers to your platform or contributors to your app, hurdles like complex or fragile tools and build processes to learn and debug all add resistance and drag, and discourage contributions. GNOME Builder can take any flatpak’d app and build it for you automatically, ready to hack within minutes.

- Different ways to distribute apps. Using OSTree under the hood, Flatpak supports single-file app .bundles, pulling from OSTree repos and OCI registries, and at Endless we’ve been working on peer-to-peer distribution like USB sticks and LAN sharing.

Nobody is trying to claim that Flatpak solves all of the problems at once, or that what we have is anywhere near perfect or completely secure, but I think what we have is pretty damn cool (I just wish we’d had it 10 years ago!). Even just in the security space, the overall effort we need is huge, but this is a journey that we are happy to be embarking together with the whole Linux desktop community. Thanks for reading, trying it out, and lending us a hand.

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

Links

Archives

- April 2024

- February 2024

- March 2023

- November 2022

- May 2022

- February 2022

- June 2021

- January 2021

- August 2019

- October 2018

- July 2017

- May 2010

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- March 2009

- January 2009

- July 2008

- June 2008

- April 2008

- May 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- June 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

- May 2005

- April 2005

- March 2005